Born in Moers, Germany, in 1964.

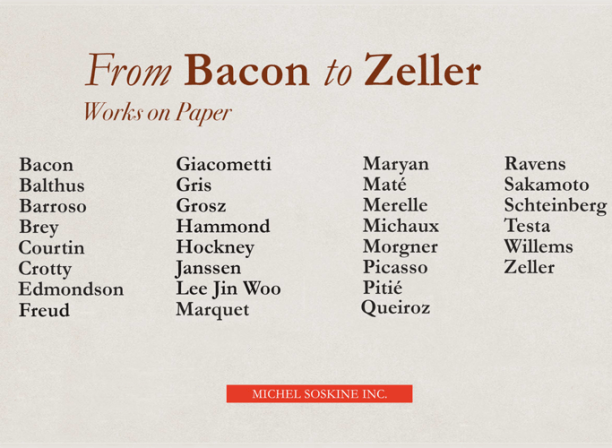

The big scenographies, urban landscapes and nature, that are not necessarily connected with the human world are the main themes of the artwork of Thomas Ravens. His philosophical studies and research, are inspired by the Situationism Philosophy of the beginning of the 70´. His ambiguous compositions are inspired by the Bauhaus, the design of Renaissance Cities of the XVI century, or the ideal of Babilonia. His compositions can also make us feel the darkness of any expressionist film by Fritz Lang or the human disaffection of Blade Runner. His scenes are usually marked by scenes of huge walls of concrete next to a crowd.

In the past years, the Berlin based artist Thomas Ravens has focused his drawings almost exclusively on landscapes and spaces, within which he combines fictitious configurations with found materials.

The watercolors prompt associations to a metropolis a vision of the future that seems eerie and uncanny. There are stadiums filled with masses of humans who take a seat, seemingly undisturbed, next to an abyss; enormous halls in which seated groups of people in vitrine-like creations and plants are superimposed with tribunes. It could be the scene of an exhibition or a fair, a massive event; that actual purpose seems indefinable. The scene is usually depicted from a central perspective – upon closer examination there are various breaks into other spaces and perspectives.

What appears to be science fiction comes from a precise observation of the present. In his paintings, Thomas Ravens fabricates much less than one initially assumes – he uses an image archive, newspaper clippings and books as his basis.

They are images of modern architecture, such as Eero Saarien’s TWA airport terminal images of clean-up after flood catastrophes, sporting events, battlefields, memorial services on New York’s “Ground Zero”.

These real events combined with staggered fabrications result in the landscape that Ravens wishes to display – it is a political landscape filled with rituals of the masses. Thomas Ravens writes in a statement on his images: “Landscape is interpreted as an over-built convex, usually in which many are observing many, and many are observing, and many observe: the football stadium is probably the most contemporary of all landscapes”.

One can imagine the simple construction. In the foreground one sees a rectangular room, unfolded Hover which a second and sometimes a third levels away, the perspective tapering into right border of the image. This is how architects have always sketched the ambiance of the streets bordering the buildings they designed. This is how public spaces have been graphically documented since the Renaissance. However the swaying groups of people and the integration of abstract household objects, is not completely along those lines – but neither was Futurism or Giorgio de Chirico’s paintings on metaphysics.

The ink drawings, watercolors and oil paintings leave no doubts. Thomas Ravens is a sophisticated artist who draws from pretty much sources. This makes his work a quiz show for prospective art historians. Tomas Ravens`s miniature figures are chilling in a flying party UFO, cruising over a green polka dot and striped hill landscape. Yet this is only one of many options for freedom. Two drawings later, a violent mass of people gather in an arena, surrounded by a dirty Project housing and iron grey catwalks. The masses stream toward a cinemascope format, white rectangle. An open-air cinema or a demonstration? One doesn´t know. Because Ravens slickly focuses the perspective of his images into a fictitious place and a non definable society that seems to be waiting for something to happen. At the same time, the stillness of the paper seems to suit him the spectacle itself has become a monument regardless if it is as a rock concert, a film premier, a sightseeing tour or an event.

However, the drawings are not merely illustrations supporting texts from the good old days of Situationism. While studying philosophy and linguistic at Bielefeld, Ravens, most likely read Guy Debord writings on cultural industry. However, what followed was his education at HdK, where practical art lessons lead to questions of position: should I participate in the system or resist it? Ravens decision is not obvious. He may maintain a fascination with the characteristics of the world of adventure at a distance by deconstructing them to the size of model airplanes and placing them in rows like a comic book sequence. But the detail-obsessed perspective also contains belittlement, if not fetishism. The abundance in artifice sometimes causes one’s interest in the actual object to disappear – the nuances in ceiling tiles in countless shades of brown becomes more important than the room below, filled with people perhaps precisely because nothing is happening down there. On the other hand, Ravens objective in his settings is not to reflect real life experience. The buildings are invented, assembled with pieces from various sources and serving, finally, as a rare show.

Ravens began in 1995 with drawings of the national pavilions at the Venice Biennale. One sees a person, coming out of a building, towards the viewer. While only an abstract wall remains of the architecture form the background, one recognizes its national classification by the sign: was that Spain, now comes Denmark? Again, this aimless order reflects the placeless by which one is struck every other year at the center of international art. In the intoxication of the events, the contours disintegrate and discursive decisions are replaced with indifferent pluralities – somewhere between trade fair and industrial exhibition. Ravens knows that this critique is also a part of the market. The depiction of the problems of the business is a part of the business. A reason to stop drawing? Definitely not. The new works have the same devilish shine on the surface, like the joyous glance into a box of pralines. Maybe at the end, the viewer realizes he has been observing himself, in the chic scenarios of the art world that Ravens has turned into an omnipresent landscape of profit.

Mass and light

Christoph Bannat

Thomas Ravens creates fantastic glossy dystopias. Light-obsessed, poetic and ironically broken. Architectures that are memorial cuboids and tank barricades in light-filled rubble landscapes. Somewhere between shopping mall, wild tent dwellings and off-the-peg sky-scrapers.

Those who believe in utopia must first believe in a future. If we Europeans think of a life in harmony, then mostly in terms of the past. And if in the present, we dream of small-scale gardens and building-group idylls rather than of complex mega-city landscapes. In this sense Ravens' works are special: they dare to take the big picture.

"You own the houses, but we own the city" reads a graffiti at Volkspark Friedrichshain in Berlin, which aptly describes the city as an arrangement of social forces, no one can avoid. Yet the concept of landscape, in addition to its cityscapes or countrysides inacting soulscapes, contains the promise of being able to stand outside as observer, to have an overview from a detached aesthetic platform.

Ravens nourishes this promise of standing outside - indeed, he starkens it by allowing the viewer to hover above things. The promise of art par excellence: to be able to detach oneself from the impact of things. The spectator of these sceneries never identifies with the human "crumb-staffage" of Ravens´ paintings.

Staffage here meaning those patterns used in architectural illustrations as placeholders for human life.Here they occur homeless, outdoors, captured in stadiums and tents, among ruins or standing on open parking decks overlooking a brave new (earthy old) world.

Two cluster of metaphors define these images: that of the city as landscape and that of light. Architecture appears here once more as a point of intersection between aesthetics, politics and the social. And just as the point is only a mathematical auxiliary construction without extension, these images are organized by the vanishing point of the perspective, evoking an endless extension of space. Stirring the desire or the anxiousness to get lost. An endlessness that is fueled by modular construction elements combined in ever new variations. No matter how individual they appear at first glance, at second glance the viewer finds a twin, a reflection, a variant. The natural blotchiness of the watercolor alone points to a form of uniqueness or individuality in a fantasy world that seems to be mysteriously created by a fanatic, omnipotent power.

With his paintings, Thomas Ravens revives and rethinks overused metaphors of light. This, too, distinguishes his works. And calls up a world of associations: from E.A.Poe's cataract of light,

in which he dooms Arthur Gordon Pym to disappear, to the inverted black-as-light box: the overexposed cinema screen before the film begins.

For Walter Benjamin, film is based on the (s)chock effect: the chock of the cut that allows the viewer no fixed point of view, as well as the fact that one can never be sure of the images themselves, as they do not linger long enough to be fully perceived. Benjamin sees film as a spectacle of moving light-images. When cinemas came up they were used to be called Lichtspieltheater (Light-game-theatre). Light shows that in our days are perfectly mobile and fit into every pocket, whose light-sources are controlled by global mega-corporations.

A (light) spectacle, of which Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, following Guy Debord's concept of Le Spectacle, say, that it glues society together yet at the same time perverting every form of collectivity. According to Hardt/Negri and Debord, "in the society of the spectacle only appearance exists and the big media companies have a kind of monopoly on what presents itself as appearance to the general public ". Thomas Ravens thinks these appearances and the masses together. Who dares to do that today. A combination that quickly evokes the light-dome fantasies of an Albert Speer. But also, leftist light metaphors such as "brothers to the sun to freedom" or even Plato's allegory of the cave. Light as a metaphor of enlightenment and deception symbolized by the sun and the torch. Near-death experiences. Light at the end of the tunnel as in Hieronymus Bosch's polyptych " Ascent of the Blessed".

The closest approach to Ravens´ panoramic drawings, is, I suggest, to think of Elias Canetti's “Mass and Power“ and the triggering experience for his research: the assassination of Walther Rathenau. Here Canetti brings together these aspects with a sleight of hand. He asks himself, what makes the masses strive towards an unknown (vanishing) point after the assassination, towards an imagination, a spectacle. And, in the first place, what makes a “Masse“ become an entity, a form. Thomas Ravens reverses this point, described by Canetti as dark, by overexposing it, in its center there is nothing to see, just the pure white of the paper. Ravens lets us participate in this spectacle, but detached- from a vanishing point of view, so to speak. While Walter Benjamin still moves in the city as a flâneur and at eye level, in Thomas Ravens' work we hover above the structures of endless mega-cities. A distance that relieves us, and, at the same time, makes us shiver, if we think of this view as one into the future.